Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement stipulates the goal to align financial flows with climate goals. In 2017, the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) committed to supporting these efforts by aligning their financial flows with the Paris Agreement, i.e. with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development, including efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. This year, a number of MDBs are planning to implement comprehensive Paris alignment approaches. Over the past five years the MDBs have already implemented various policies and tools intended to support the alignment of their investments with climate goals.

Following up on overviews of these tools provided in our 2018 report and 2021 update, this blog post provides a summary of the tools and traces the progress made by the MDBs since 2021. It looks at changes (highlighted in bold) in the policies and strategies of seven MDBs - namely the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the European Investment Bank (EIB), the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). In view of this picture, it then sets out expectations for the comprehensive Paris alignment methodologies in which those efforts are to cumulate and places them within the context of the broader discussion on reforming MDBs to be better able to address global challenges.

Overall, we found that the banks still require significant progress to meet their commitments. This is particularly urgent with regards to implementing fossil fuel exclusion policies but also concerning the standardization of other instruments and the provision of more systematic support for green development. Individual banks are indeed making progress, but their efforts are not shared across the group.

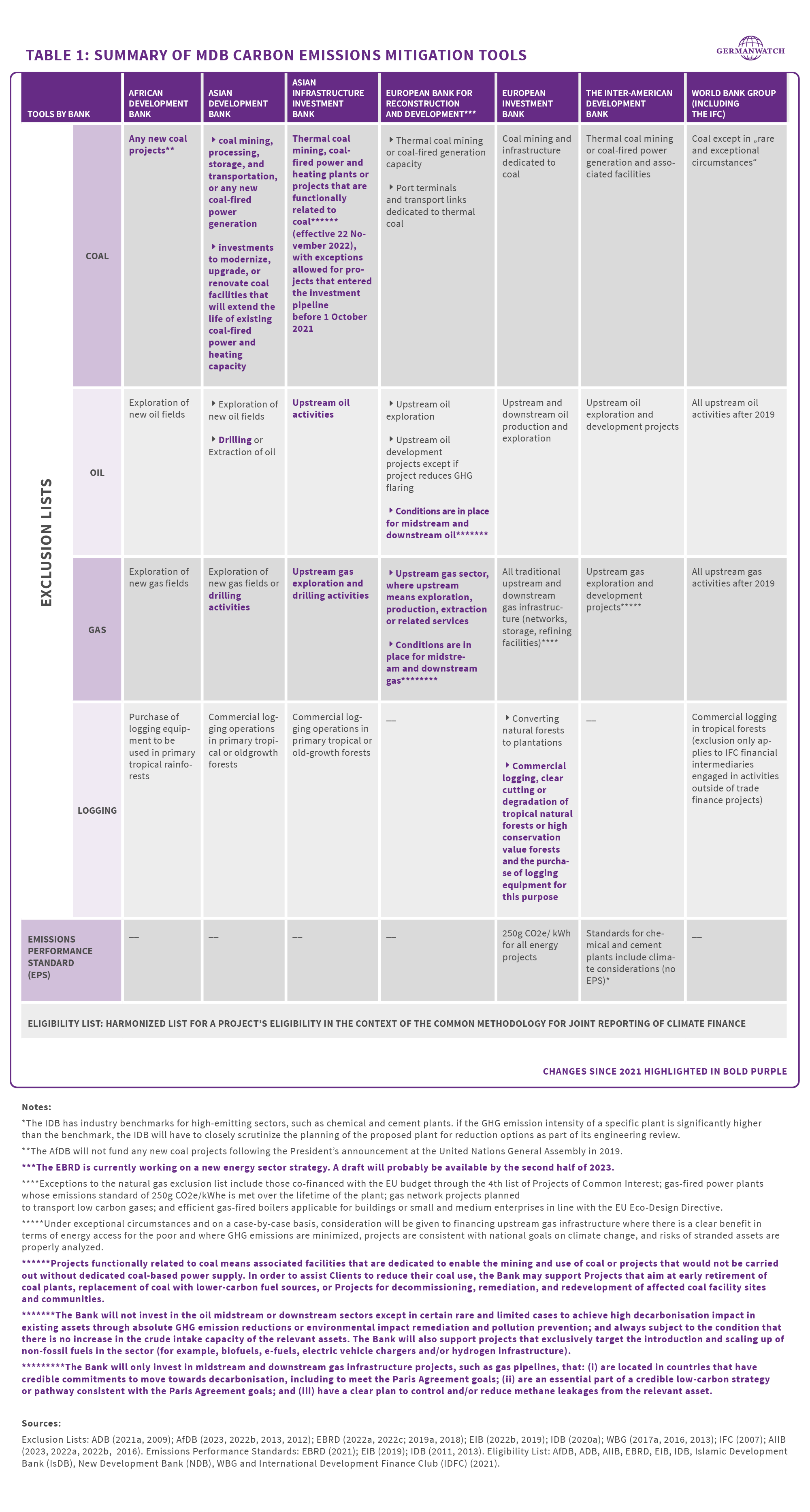

Fossil fuel exclusion policies have expanded, especially for coal, but there is still room for further expansion and standardization across all institutions. The overall lack of standardization and ambition is clearly reflected in the extremely meagre joint MDB list of universally non-aligned activities (“exclusion list“) which does not list any other fossil fuel-related activities except extraction and electricity generation from peat and coal. Of the seven MDBs analysed, four have updated their individual exclusion lists (see table 1). All seven MDBs now exclude (most) investments in coal projects, albeit to differing extents. Exclusions for oil and gas investments vary across MDBs: The EIB is the only MDB to exclude downstream oil and gas. The EBRD limits midstream and downstream oil to some exceptions and sets out criteria for financing midstream and downstream gas. Regarding upstream oil, only the WBG and the AIIB exclude all upstream oil activities, whilst AfDB, ADB, EBRD, EIB and IDB exclude upstream oil exploration and at times also the drilling, extraction or production of oil. Regarding upstream gas, only the WBG, the EIB and the EBRD exclude all upstream activities, with the EIB naming certain exceptions - AfDB, ADB, IDB and AIIB exclude upstream gas exploration and at times drilling activities or gas development projects.

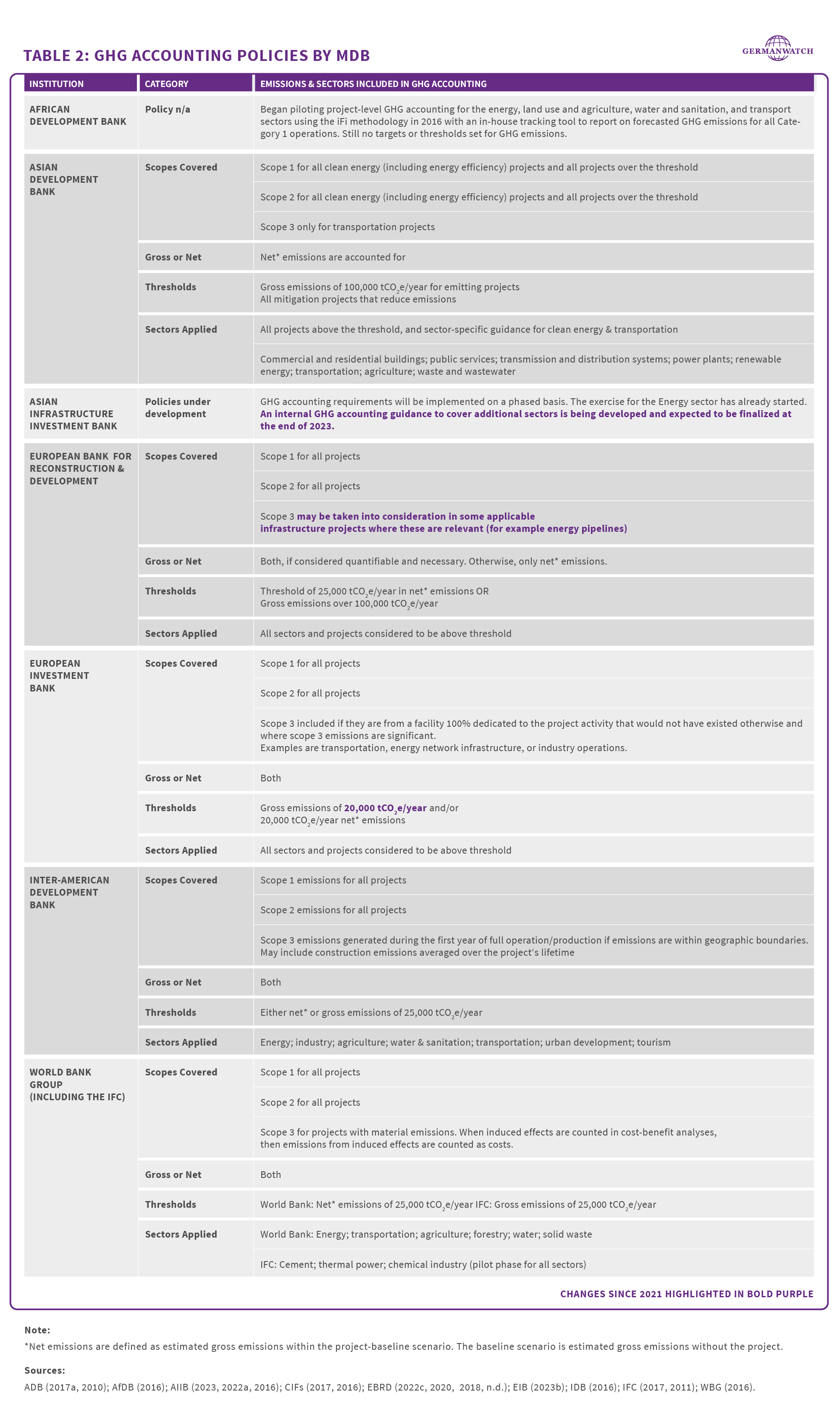

Further room exists for MDBs to standardize how they count and price emissions. The lack of a unified approach to greenhouse gas accounting and its application to scope 3 emissions remains unchanged. Three MDBs have partially updated their GHG accounting policies and strategies (see table 2): The EBRD now considers scope 3 emissions in some infrastructure projects where these are deemed relevant (e.g., energy pipelines). The EIB has lowered its gross emissions threshold from 100,000 tCO2e/year to 20,000 tCO2e/year. Finally, whilst the AIIB does not have a published GHG accounting policy, it is implementing GHG accounting on a phased basis and is working on internal guidelines to cover additional sectors (besides energy) by the end of 2023. The EIB is still the only MDB to apply an Emissions Performance Standard (250 gCO2 per kWh for all energy projects), which nevertheless still lies above the emissions threshold stipulated by the EU taxonomy of 100 gCO2 per kWh.

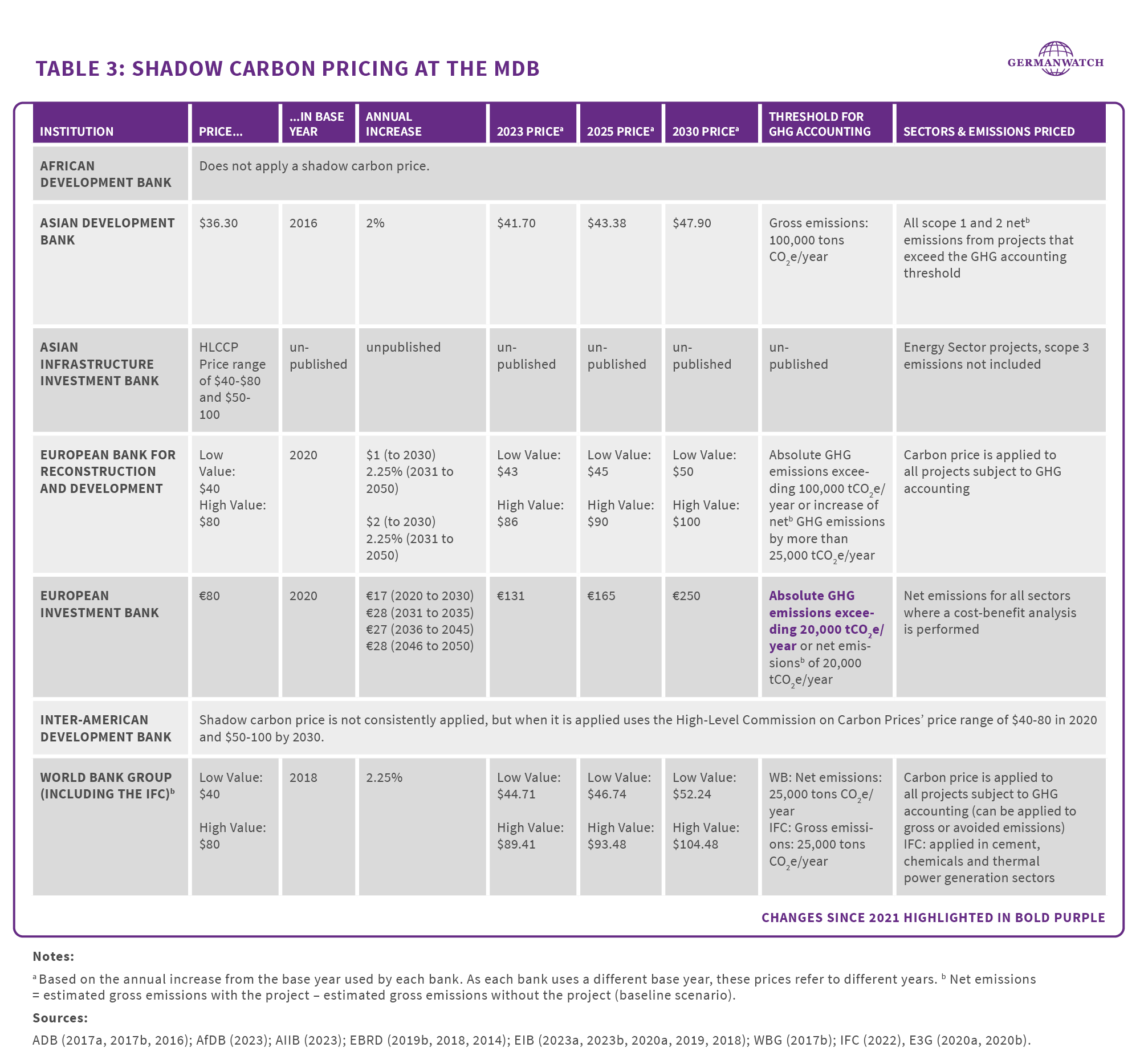

Shadow carbon pricing has not changed at any MDB compared to 2021 (see Table 3). The EIB applies the most ambitious shadow carbon price with a value of €165 in 2025 and €250 in 2050. The EBRD, the WBG and the AIIB align closely with the price recommended by the High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices (HLCCP). In contrast, the IDB does not consistently apply a carbon price and the AfDB does not apply one at all.

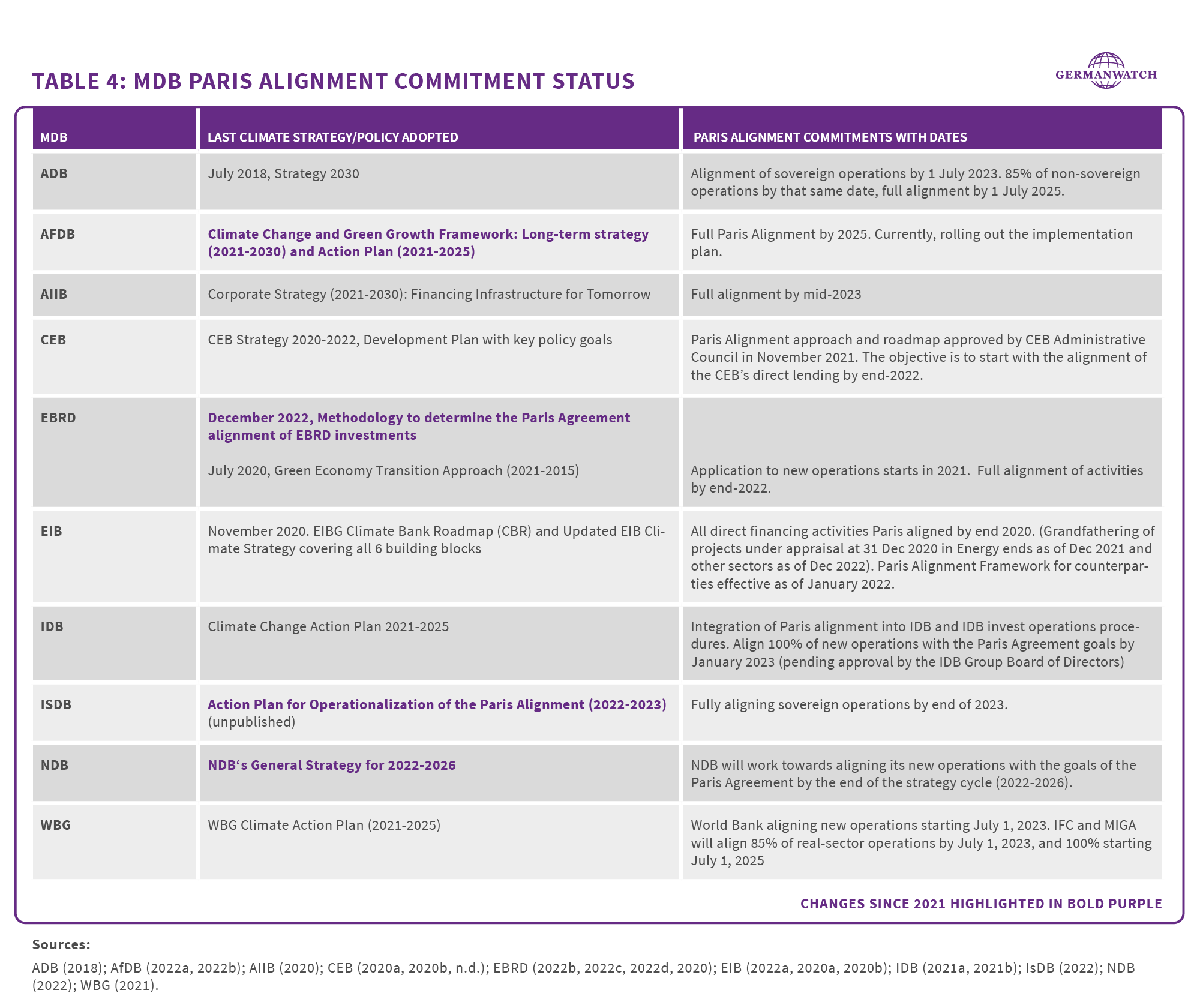

Official Paris alignment dates are set, with 2023 as a decisive year. Importantly, eight MDBs have now set firm deadlines for achieving full Paris alignment (also including indirect investments) (see table 4). In addition to the seven MDBs reviewed, notably also the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) has now developed an Action Plan to align sovereign operations by the end of 2023. Still without an alignment date, the New Development Bank (NDB) has at least committed to “work towards” Paris alignment under its General Strategy for 2022-2026. So far only the EIB and the EBRD have published comprehensive methodologies covering all their finance instruments and are applying them. Like the EBRD, the IDB had also committed to full Paris alignment by January 1, 2023; its Paris alignment methodology is already being applied internally but has not yet been published. Also the Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB) aims to align its direct investments with Paris goals since end-2022.

The year 2023 will be decisive insofar as three more MDBs (ADB: sovereign operations, AIIB, WBG: IBRD/IDA) have pledged to align (most of) their portfolios during this year (see table 4) and are expected to publish respective approaches. It remains to be seen whether these methodologies (and their application) will bring about the quantum leap that is needed to bring MDBs’ financial flows in line with the Paris climate goals. The joint MDB methodology itself is not convincing enough.

Joint MDB Paris alignment methodology too general and lacking ambition

Expanding on the tools and commitments discussed above, the MDBs have been working on a comprehensive joint methodology to determine the Paris alignment of all their investments. Some MDBs have been piloting an assessment framework focussing on the alignment of their direct investments since 2021, but it leaves various questions unanswered in terms of its interpretation and the extent of its actual application by individual banks remains unclear. The alignment of indirect investments and especially policy-based operations, in turn, has long remained a blind spot. At COP27, the MDBs gave an update on their Paris alignment efforts and, for the first time, this included a high-level approach to assessing the alignment of policy-based financing (PBF). While the PBF approach is too general to thoroughly judge its quality, there seem to be important shortfalls: The lock-in test lacks a clear reference to 1.5°C compatible pathways and begs questions regarding “lower-carbon means” as a potential loophole for the continued financing of fossil fuel activities. The PBF approach also repeats a more general problem of the joint MDB Paris alignment methodology which seems to focus mainly on doing no harm to climate goals, reserving the task of actively supporting the climate transition to a limited share of their portfolio under their climate finance targets. Given that a lack of transformative action will eventually result in harm in the very near future, this is, however, an unhelpful dichotomy. While not all Paris aligned projects will evidently contribute to climate finance, the MDBs should use their Paris alignment approach to direct a large share of their portfolio at generating positive climate impacts and ideally at being transformative.

Amidst calls for evolution and reform of the international financial architecture: MDBs need to make Paris alignment a tool to support the transition

In view of multiple crises – energy, food, debt, climate, and health – and with associated financing needs skyrocketing, concerns are mounting that current international financing structures including the Bretton Woods Institutions are no longer adequate for supporting development under these circumstances. Calls for respective reform include, e.g., the G7+3 shareholder request for an evolution roadmap by the World Bank Group (informed, inter alia, by the Capital Adequacy Framework Review commissioned by the G20), the UNFCCC members’ reform call to MDBs and their shareholders at COP27, and the Bridgetown agenda advanced by Barbados and supported by France in particular. The discussion also revolves around the need for international financial institutions to protect and foster global public goods including climate.

Ambitious Paris-alignment methodologies can act as effective tools to support the climate transformation and can play an important part in addressing the crisis cascade. To do so, they need to ensure that all MDB financing seeks to support the transition wherever possible. It is now up to the individual banks to scale up ambition and ensure effectiveness when translating the joint high-level approach into their own processes. More specifically, MDBs should:

- Scale up analysis and technical assistance for climate action. MDBs should systematically integrate not just climate risks but also green development opportunities and just transition considerations in diagnostics and support consistent application by staff with guidance, training and accountability mechanisms. What is more, MDBs should systematically support country strategies with technical assistance to integrate climate risks into long-term macro-fiscal assessments, and to assess institutional capacity for climate action. Not least, MDBs should conduct impact assessments to distill lessons learned for improving climate impact. (Our 2022 paper on Aligning policy-based finance with the Paris Agreement demonstrates the relevance of these recommendations focusing on policy-based finance.)

- Make policy-based financing a tool for climate action. Banks that provide policy-based financing will need to ensure that policy actions do no harm to climate objectives and, wherever possible, identify opportunities for transformational policy change together with client countries. They also need to think about setting additional incentives for countries to request that type of financing. As we show, this includes considering climate from step one of the process of designing a policy-based operation, including in diagnostics, country dialogue and strategy as well as donor coordination.

- Stop financing fossil fuel activities. Further investments in fossil fuels are not able to support sustainable development. To align their finance with the mitigation goals of the Paris Agreement and make it compatible with a 1.5°C pathway, MDBs need to expand their exclusion list as soon as possible as part of their Paris alignment efforts, to include all financing (both direct and indirect) related to

- the expansion of oil and natural gas production

- new infrastructure for further processing or transportation of coal, oil and natural gas, e.g., new gas pipelines, LNG export terminals

- activities that increase the demand for natural gas (especially considering that renewable power generation has largely achieved cost parity), e.g., new gas-fired power plants that are not primarily used to meet peak load and stabilise grid frequency, oil for heating, or gas for cooking and heating when renewables combined with electrification would be an alternative (see IPCC 2021, IPCC 2022, IEA, NewClimate, NewClimate/Germanwatch, IISD).

References for the tables 1-4

We contacted climate staff at ADB, AfDB, AIIB, EBRD, EIB, IDB and WBG to confirm our research. To date, we received feedback from AfDB, AIIB, EIB and IDB. To see the complete list of references, please click here.