This blog series aims to debunk ‘myths’ about trade-offs between climate action and development. Addressing political decision-makers, practitioners in multilateral development banks as well as staff of civil society organisations and the interested public, three blog posts will provide them with evidence to refute widespread misconceptions about the effects of climate action on development. They will also include recommendations for multilateral development banks on how to contribute to strengthening the link between climate action and development and thereby highlight win-win opportunities and avoid trade-offs.

Over the past decade, the urgent need for global climate action finally paved its way through to national and international politics and largely enjoys public recognition today. However, preconceptions about various perceived trade-offs impede much needed climate action. One concern that is prevalent especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is that climate policies might undermine (short-term) economic development by purported high opportunity costs or co-impacts of climate action. This “myth” is fuelled by three main assumptions. First, that climate action will raise the cost of living, as many green projects, e.g. renewable energies, are perceived as being more expensive and linked to higher costs for consumers. Second, that high opportunity costs will exacerbate poverty. And third, that more ambitious climate policies will impede economic growth, due to for example the fear of additional investment costs or through a loss of competitiveness. Some policy-makers draw on these arguments to push forward fossil development rather than seeking cleaner alternatives. In the following, we will explain why climate action does not hinder economic development, and in fact promotes it.

There is growing concern that the world is on the verge of facing a deep economic crisis. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has caused food, fertiliser, and energy prices to surge. Inflation, geo-economic fragmentation, and supply chain problems send shock waves across the globe. On top of that, climate induced catastrophes worsen the situation.[1]

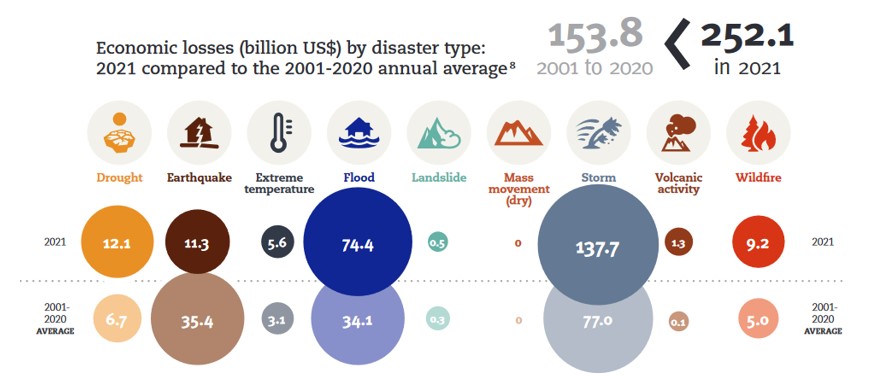

Figure 1: Comparison of economic losses (bn USD) by disaster type: 2021 and annual average of 2001-2020

In highly indebted countries such as Sri Lanka, social unrest has erupted. The looming economic crisis in large parts of Africa threatens food security to an extent not seen since the 1950s. These setbacks come at a time when huge efforts and investments in the global transition to greenhouse gas neutrality and climate resilience are required.

In this context, calls remain to de-prioritise climate action and instead invest in preventing the erosion of living standards and compensating macroeconomic imbalances. This, however, would be fatal. Deprioritising climate action would inevitably worsen the problems in the medium and long-term: According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 3.3 billion people are currently living in countries that are vulnerable to climate change impacts. By 2050, the IPCC expects this number to have increased to an extent that almost everyone living on the planet will be affected.[2] Climate action is therefore more urgent than ever before and even turns into a condition for sustainable economic development. As we will see in the following examples, despite persisting misconceptions about the opportunity costs of climate action, it is scientifically evident that climate action provides significant development co-benefits.

CLIMATE ACTION REDUCES RATHER THAN

INCREASES THE COST OF LIVING.

There are concerns that climate action will increase the cost of living, mainly because of the assumption that energy prices are likely to increase with the transition to renewable sources. Yet is this fear justified?

Analyses show that rising energy prices are particularly problematic for countries that are heavily dependent on energy imports.[3] If these countries are additionally highly indebted, energy price shocks such as the current one strain their budgets.[4]

Nevertheless, even coal producing countries without such dependencies have faced severe setbacks by global increases in energy prices, such as in India. While higher prices of energy imports have negatively impacted economic development, the overall price increase has also led to higher prices for domestic coal.[5] Last year already, low stockpiles and rising power demands, especially during the increasingly hot summer months, have complicated the plans to expand domestic coal production. Instead of being able to work towards becoming independent from coal imports, these circumstances contributed to a spike in energy prices and an even heavier dependence on coal imports.[6] On top of that, 40% of India’s thermal power plants (nuclear energy, gas, or coal-fired power plants) are exposed to shortages of water, which they need for cooling, and thus face the risk of forced power outages because of drought. By 2030, this problem will expand to 70% of India’s thermal power plants as increasingly higher temperatures aggravate water stress in the country.[7]

As opposed to this, energy prices for renewable energy remain more stable and more resilient to water stress. Since their energy supply eliminates the need for a fuel to be transported, supply chain disruptions do not affect prices as easily as is the case with fossil fuels.[8]

Countries whose energy production is largely secured by domestic renewable energy are therefore less vulnerable, which directly benefits lower-income groups[9] and economic growth. In Europe, for instance, households with their own solar PV panels are less affected by recent electricity price jump. On average they save about 60% on their monthly energy bills.[10]

Ending poverty is Kenya’s number one priority, a country with a population of 45% living below the poverty line. Climate change is already undermining anti-poverty efforts with droughts becoming more frequent and severe in recent years, turning into a major threat leading to famine, conflict, and displacement, in particular in the north of the country.[11] Poverty, climate change, and environmental integrity are regarded as interconnected societal challenges in Kenya, and are addressed in a set of policies[12] including for example the Climate Change Bill, the National Climate Change Response Strategy, and the National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP).[13][14]

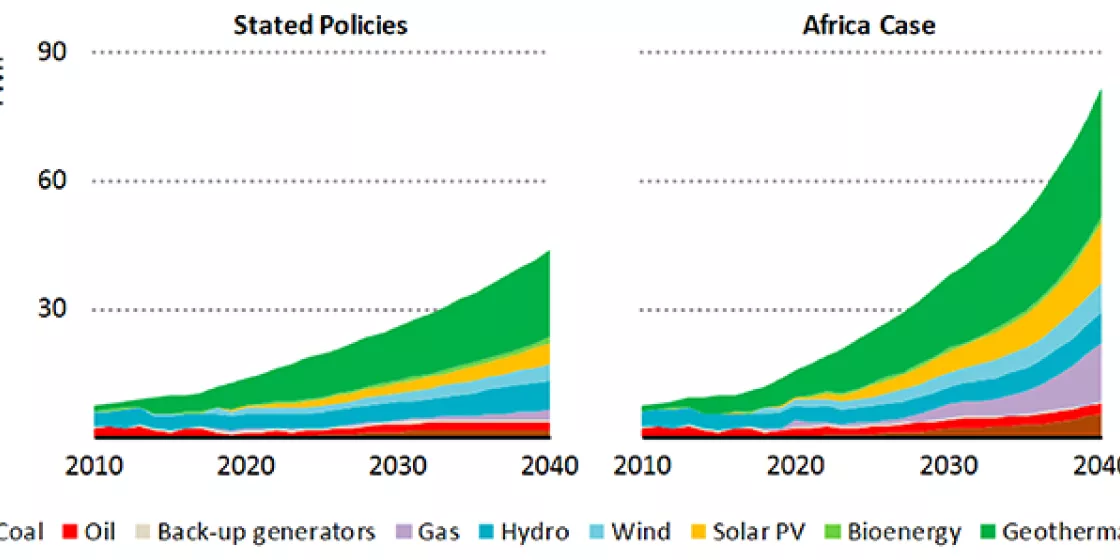

One opportunity to alleviate poverty in Kenya is to expand renewable energy. Early climate action and vast wind, solar, and geothermal energy resources have allowed Kenya to become a leader in renewable energies, ranked 12th in the world and first in Africa in terms of renewable energy deployment.[15] The country is a leader geothermal energy taking advantage of the opportunities in the Great Rift Valley.[16] Kenya aims to double its geothermal capacity by 2030, and even export know-how to neighbouring countries.

Figure 2: Kenya elecricity generation by technology

CLIMATE ACTION HAS GREAT POTENTIAL TO

REDUCE POVERTY. CLIMATE INACTION WILL

INCREASE POVERTY.

Another frequently expressed concern calls ambitious climate policies a luxury that is too expensive for countries whose priority is overcoming extreme poverty.

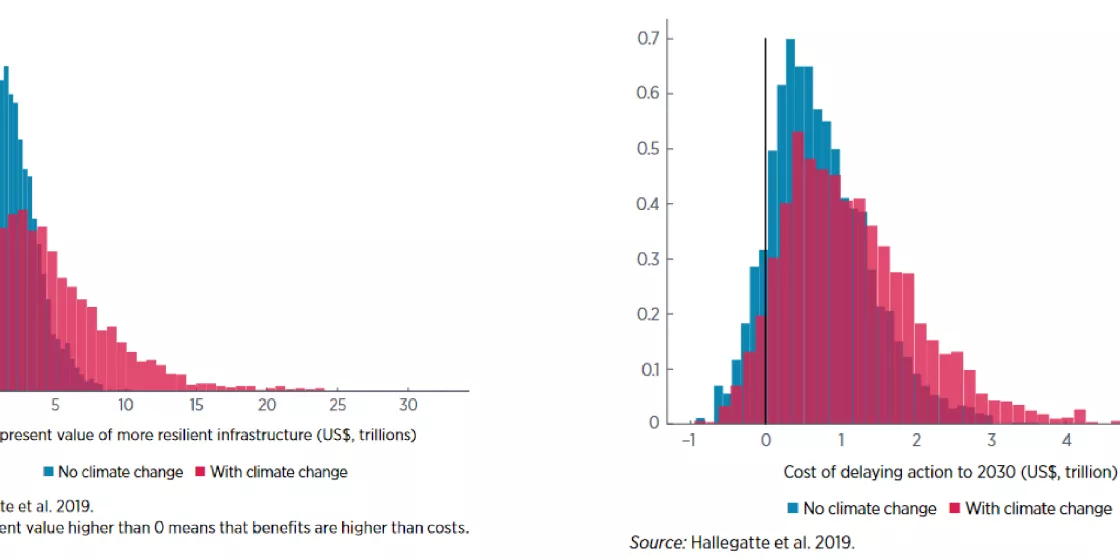

Yet this criticism does not stand up to scrutiny either. As a study by the World Bank shows, costs of building new climate resilient infrastructure are relatively small in comparison to baseline infrastructure investment needs and thus do “not affect current affordability challenges.”[19] Moreover, as figures 2 and 3 indicate, investments in more resilient infrastructure show a high benefit-cost ratio. While the research indicates that large financial losses are in fact unlikely, climate resilient infrastructure is rather cost-effective and could even generate benefits.[20]

Figure 3: Cost effectiveness of investment in resilient infrastructure (left) and costs of inaction (right)

Investing in climate resilience is indeed not only cost-effective, but also essential to avert a rise in poverty: Analyses show that poor countries and households suffer above-average economic losses from climate change, making it a top driver of poverty.[21] This is particularly true for semi-arid and agriculturally dependent countries, cyclone affected countries, countries exposed to sea level rise and countries in which especially the poor are highly dependent on fisheries. Climate change impacts thereby undermine efforts for inclusive development and often affect the poorest the most.[22]

Climate adaptation, climate-sensitive social safety nets, and climate risk transfers stabilise and increase the income of rural households whose livelihoods are often highly dependent on ecosystem services such as regulating services like flood protection or provisioning services like timber.[23] Furthermore, investments in climate resilient pro-poor infrastructure, such as coastal protection, resilient housing, transport, and agriculture, have positive effects on mitigating climate-induced damages and thereby stabilise local costs of living.

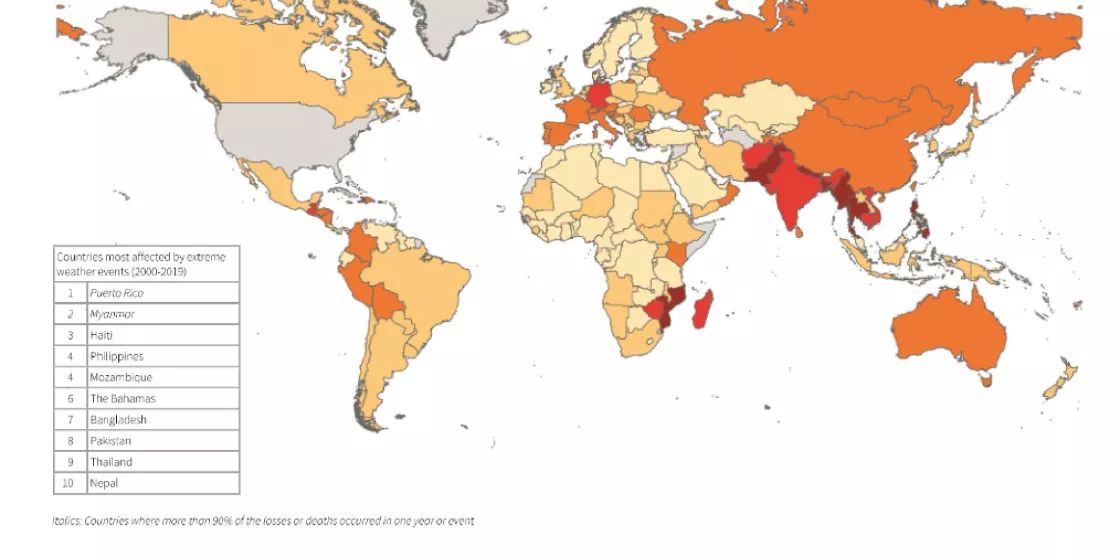

Constant economic growth is Bangladesh’s top priority. The country is scheduled to graduate from the status of a Least Developed Country by 2026. With its real GDP rapidly growing,[24] Bangladesh belongs to the “Next Eleven”[25] countries.[26] However, aggravating economic damages due to extreme climate events increasingly threaten Bangladesh’s development.[27]

Figure 4: Global Climate Risk Index 2000-2019

These considerations led to a review of the PSMP and eventually the cancellation of the expansion plans for coal-fired power plants[32] and the approval of the Mujib Climate Prosperity Plan (MCPP)[33] in 2021. The MCPP links climate action to development planning in order to achieve robust socio-economic development based on climate resilience and green economic growth. With this approach, the government seeks to mitigate catastrophic climate impacts on the economy which could accumulate to yearly losses of 6.8% in GDP by 2030 in a business as usual scenario.[34] This proves that climate action is not only financially feasible for poorer countries but that it can even provide various benefits.

CLIMATE ACTION STIMULATES ECONOMIC

GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT. INACTION HAS

THE OPPOSITE EFFECT.

Furthermore, some worry that ambitious climate action might slow down economic growth. However, this also proves to be incorrect.

Future economic prosperity depends on limiting global warming to well below 2 degrees. In the long run, climate-induced damages are expected to increase to USD 438 billion annually in the 2030s, rising up to USD 1.067 billion by 2050 if current trends continue.[35] The IPCC identified over 130 key risks across regions and sectors, including critical infrastructure, networks and services, living standards, health, food and water security. In the light of this widespread potential for risk, the IPCC calls for scaling up investments in transformative adaptation by 3 to 6 times by 2030.[36] For example, investing in climate-resilient infrastructure to improve adaptation is estimated to generate four times more benefits than costs.[37] Instead of slowing it down, ambitious climate action can thus in fact contribute to economic growth.

In another example, even in the short term, climate action can have a positive impact on the economy, a study on decarbonisation in the US shows. While it is true that climate mitigation efforts will mostly pay off and save money in the long term, emission reduction efforts can already provide short-term economic benefits that can outweigh costs within a decade thanks to health improvements resulting from the improved air quality.[38]

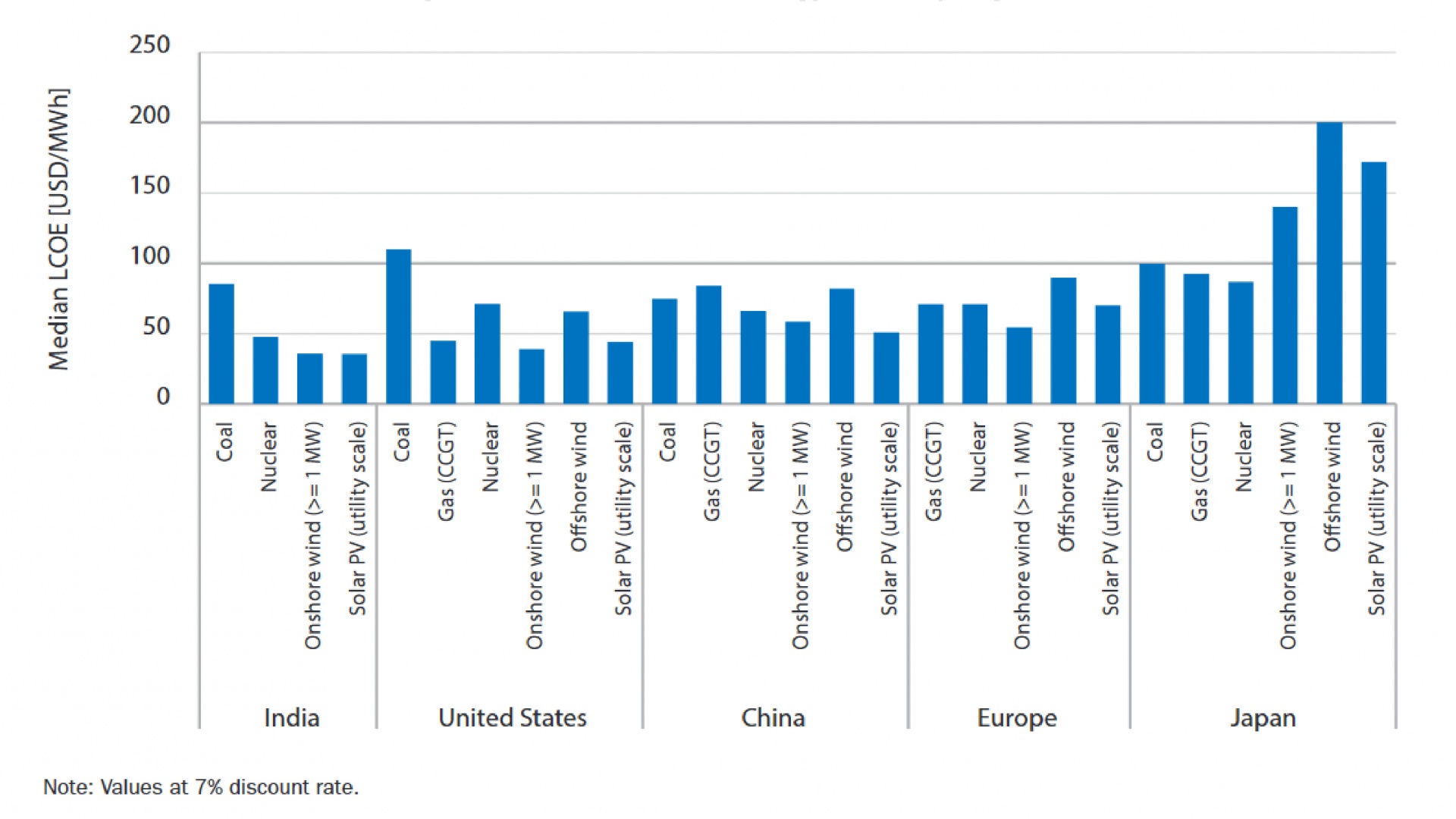

At the same time, scaling up investments in decarbonisation globally now will reduce the costs incurred by economies to compensate for climate-related damages in the future. Continuing to invest in fossil energy sources would create a carbon lock-in and risk turning into stranded assets in the near future, making access to affordable renewable energy a key driver of economic growth. The International Energy Agency (IEA) has shown that in regard to the levelised costs of electricity generation, onshore wind and solar PV are the most competitive if deployed at large scale, and that coal-fired power generation is no longer competitively viable. The analysis revealed that for the majority of countries and regions evaluated in the report, renewables represent the most cost-effective solution (see figure 5).[39]

Figure 5: Median technology costs by region

The same is true for power plants fuelled by fossil gas, as even before the current crisis of fossil fuel prices, the marginal operating cost of fossil fuel-fired plants was higher than that of onshore wind and solar PV.[40]

This is mainly thanks to the sharp decline in the cost of renewable energy technologies. On global average, the electricity generation cost of onshore wind dropped by 45%, of PV by 56%, and of battery storage by 64% between 2015 and 2019 and is anticipated to further decrease in the future. Investments in renewable energy have thus more potential to generate financial returns than investments in fossil energy sources, especially given the highly volatile global market prices for fossil fuels.

Apart from the apparent economic benefits through investments, ambitious climate policies are also likely to have a positive impact on employment: Projections indicate that in an advanced energy transition scenario, 46.1 million jobs will be created in the energy sector by 2030 in contrast to only 27.3 million in the reference scenario.[41]

THE CRITICAL ROLE MULTILATERAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS CAN PLAY

Created by public mandate and capitalised with taxpayer funds, the most important mission of multilateral development banks (MDBs) is to promote the socio-ecological transformation on the way to zero poverty as the key challenge of our time.

As the cases of Bangladesh and Kenya show, ambitious climate action in LMICs bears huge potential to mobilise sustainable development co-benefits. Enabling national policy frameworks, investments in renewable energy, and access to efficient technologies are pivotal for success—and in both cases, development banks have played an important role in stimulating innovative planning.[42]

There are various measures MDBs can take to strengthen win-win effects between climate action and development.

Firstly, MDBs can put more effort in highlighting the economic and social benefits of climate action as well as the risks of inaction to their partners. They can systematically help them identify and prioritise opportunities for high-impact climate action and for securing a just transition. Currently, country strategies, such as the World Bank Group’s Country Climate and Development Reports, diagnostic tools and priorities as well as project design processes do not adequately consider climate risks nor do they identify green development opportunities.[43]

- On the one hand, these blind spots need to be addressed by using metric key risk indicators to quantify physical climate risks, lock-in risks as well as the stranded asset risk of carbon-intense infrastructure.

- On the other hand, partner country engagement and bank-internal processes need to be revised so that green development opportunities and climate co-benefits become an integral part of country strategies, sector strategies, and project design processes.

Secondly, MDBs can set financial incentives and increase fiscal space for more ambitious climate action by providing LMICs with more highly concessional finance for climate action.

- To meet the high upfront costs of the transition to renewables, MDBs can provide concessional loans with long maturities, leveraging additional private investment. Supporting strategic climate flagship projects with sustainable development co-benefits and scaling potential represents a particularly promising measure for MDBs.[44] A good example of such a project is the Lake Turkana Wind Energy Project, Africa’s largest wind farm and a flagship project to implement the Kenyan Vision 2030. Co-financed by several donors, including the African Development Bank and the European Investment Bank, it generates reliable, low-cost 850KW of electricity, representing 17% of the national installed capacity. Savings for fuel displacement costs were estimated at USD 150 million annually.[45]

- Moreover, investment in adaptation measures is key for securing sustained economic development by making sectors such as agriculture, water, and sanitation more resilient. MDB concessional financing, especially in the form of grants, is even more important in this respect as adaptation measures often do not generate a direct return on investment. One part of the problem is that there is too little highly concessional climate finance. As the IPCC says, most climate finance is focused on mitigation, and there is a widening disparity between the estimated costs of adaptation and documented finance allocated to adaptation – with the largest gaps among lower income population groups. This makes it difficult – especially for highly indebted countries – to finance these projects and to repay loans for adaptation measures and to attract private investors. Albeit minor points of critique, such as a more systematic translation into projects, the Water Sector Strategy[46] of the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank can serve as a good practice for the translation of the Paris Agreement’s climate resilience goal into a sector strategy.

- MDBs can also provide more disaster risk finance to reduce climate-related disaster risks and address related economic damages. The World Bank’s Deferred Draw-Down Options for Catastrophe Risk[47] are a good example of an instrument that is both preventive and compensatory.[48]

Thirdly, MDBs are strategically positioned to provide LMICs with technical support for mitigation and adaptation, and thus to support effective climate action for development.

- This can include support to ratchet NDCs,[49] long-term strategies, national adaptation plans, disaster risk management systems, or the design of social compensation in carbon pricing mechanisms, for example.[50]

- In addition, MDBs can provide technical assistance on the sectoral level, for instance, for the decarbonisation of the power sector. They play a key role in technology transfer for the energy transition by financing transfer for clean energy as well as offering sector-specific support via capacity building, knowledge sharing, and policy advice.[51]

- Moreover, de-risking tools, such as guarantees or insurance, can make investments more attractive for private financiers, thereby contributing and accelerating to sectoral transformations.[52]

KEY TAKEAWAYS ON HOW TO TURN INSIGHTS INTO ACTION

-

Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris climate goals are interdependent. Although there is a common belief that ambitious, well-designed climate action leads to a higher cost of living and that it implies more poverty and less growth, quite the opposite has proven to be the case. Significant sustainable development benefits will only materialise if climate policy is properly conceptualised, effectively implemented, sufficiently financed, and flanked by social policy.

-

Delaying ambitious climate action is a recipe for disaster. While scientific scenarios clearly show that immediate and massive efforts are necessary to avert a climate catastrophe, present actions of political decision-makers and investors do not sufficiently reflect the urgency of the situation. The 2020s are considered the critical decade of implementation, making it high time for political decision-makers, governments and multilateral development banks to maximise their efforts and do everything in their power to reach the internationally agreed limit on global warming. This entails aligning both implementation strategies and investments to the climate goals of the Paris Agreement

-

Challenges need to be overcome to leverage climate action for economic development. Stakeholders involved in climate and development action urgently need to improve their cooperation and coordinate their efforts more effectively. The following should be their respective top priorities:

-

Governments should align their development, finance, and economic policies with the goals of the Paris Agreement, and ensure that their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) are updated but also aim to mobilise a maximum of sustainable development co-benefits.

-

Development Banks should be transformed into sustainability and climate banks that operate in full alignment with the Paris Agreement and other than technical support also provide concessional subordinated loans that leverage private investments on the required scales.

-

Civil society organisations should serve as transition change agents, be it as think tanks, pioneers, watchdogs, campaigners, or, most importantly, as advocates for the rights of the most vulnerable demographic groups and territories, providing climate justice to them.

-

[1] https://reliefweb.int/report/world/2021-disasters-numbers

[2] https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/

[3] https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/energy-prices

[4] https://www.brot-fuer-die-welt.de/fileadmin/mediapool/downloads/fachpublikationen/analyse/Analyse_102_English.pdf

[5] https://www.icis.com/explore/jp/resources/news/2022/04/01/10749931/insight-high-energy-prices-to-hit-india-industries-hard

[6] https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/products-services/coal/global-coal-alert

[7] https://www.wri.org/insights/40-indias-thermal-power-plants-are-water-scarce-areas-threatening-shutdowns

[8] https://www.wri.org/insights/why-renewable-energy-solution-high-prices

[9] https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/4ed140c1-c3f3-4fd9-acae-789a4e14a23c/WorldEnergyOutlook2021.pdf

[10] https://www.pv-magazine.com/2021/11/12/european-electricity-price-hikes-supercharge-solar/

[11] https://www.wwf.de/themen-projekte/projektregionen/kenia-und-tansania/duerre-in-kenia

[12] https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-45106-6_118

[13] The NCCAP for example sets out to achieve sustainable development via enhanced food security and resilience of agricultural systems; ensuring access to and efficient use of water; land protection and rehabilitation; strengthening of resilience with regards to health, sanitation, and human settlements; developing an affordable transport system, reducing fuel consumption, and boosting of renewable energies.

[14] https://www.iisd.org/articles/adapting-to-climate-change

[15] 85% of the total energy supply.

[16] https://www.thinkgeoenergy.com/significant-increase-in-geothermal-development-in-kenya/ : 863 MW of installed capacity in 2021.

[17] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-07-19/kenya-aims-to-double-geothermal-capacity-by-2030

[18] https://borgenproject.org/geothermal-power/

[19] https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31805, p.105

[20] https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31805

[21] https://www.brot-fuer-die-welt.de/fileadmin/mediapool/downloads/fachpublikationen/analyse/Analyse_102_English.pdf

[22] https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/

[23] https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/69863/1/MPRA_paper_69863.pdf

[24] https://www.statista.com/statistics/438214/gross-domestic-product-gdp-growth-rate-in-bangladesh/

[25] Next Eleven or N11: A group of 10 countries (Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, Turkey, South Korea, and Vietnam) with emerging economies that, due to their fast economic growth, have the potential to belong to the world’s largest economies in the future.

[26] https://energyeducation.ca/encyclopedia/N11_countries

[27] https://www.germanwatch.org/sites/default/files/Global%20Climate%20Risk%20Index%202021_2.pdf

[28] https://www.uts.edu.au/sites/default/files/2019-08/Bangladesh%20Report-2019-8-17.pdf

[29] Accumulated investment costs to achieve 100% renewable energy supply in the electricity sector by 2050 are over-compensated by fuel cost savings in the same period of about USD 3-7 billion. In a business as usual reference scenario, the savings would amount only to $ 2.4 billion.

[30] Ibid, page 82

[31] Ibid, page 88

[32] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bangladesh-energy-climate-change-coal-idUSKCN2E410H

[33] https://mujibplan.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Mujib-Climate-Prosperity-Plan_ao-21Dec2021_small.pdf

[34] The approach has a strong focus on protecting micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSME), responsible for 75% of the employment and 40% of the GDP, by providing them with access to climate risk insurance and finance. With lower risks, MSME can grow more consistently. The MCPP also contemplates that the growing share of renewables will lead to lower energy prices, and create 40,000 jobs by 2030.

[35] https://www.brot-fuer-die-welt.de/downloads/analyse102-climate-change-dept-covid19/

[36] https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/

[37] https://gca.org/reports/a-green-and-resilient-recovery-for-latin-america/

[38] https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2104061118#fig07

[39] Calculation based on the assumption of an only moderate carbon price of $30 per tonne; https://www.iea.org/reports/projected-costs-of-generating-electricity-2020

[40] https://irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2022/Jul/IRENA_Renewable_Power_Generation_Costs_2021.pdf

[41] https://www.greenpeace.de/publikationen/greenpeace_energy-revolution_erneuerbare_2050_20150921.pdf

[42] https://pubs.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/17169IIED.pdf

[43] https://www.germanwatch.org/en/84652

[44] https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/evaluation-document/640341/files/te-climate-change.pdf

[45] https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/lake-turkana-wind-power-project-nominated-power-deal-of-the-year-in-2014-13886

[46] https://www.aiib.org/en/policies-strategies/operational-policies/public-consultation-draft-water-sector-strategy/.content/_download/Water-Strategy-Final.pdf

[47] https://web.worldbank.org/archive/website01265/WEB/IMAGES/CATDDOPR.PDF

[48] https://climate-insurance.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Climate_Disaster_Finance_Agenda_MCII_June2022_final.pdf

[49] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/06/22/world-bank-group-increases-support-for-climate-action-in-developing-countries

[50] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/05/24/global-carbon-pricing-generates-record-84-billion-in-revenue

[51] https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/governing-climate-change/transferring-technologies/BD3D8AE62A1F138D023994C79D53F32D

[52] https://www.wri.org/insights/insider-expanding-toolbox-glimpse-new-generation-mdb-de-risking-approaches

Image sources:

Figure 1: CRED. 2021 Disasters in numbers. Brussels: CRED; 2022, https://reliefweb.int/report/world/2021-disasters-numbers.

Figure 2: IEA (2019), Kenya Energy Outlook, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/articles/kenya-energy-outlook. All rights reserved.

Figure 3: Hallegatte, Stephane; Rentschler, Jun; Rozenberg, Julie. 2019. Lifelines: The Resilient Infrastructure Opportunity. Sustainable Infrastructure;. Washington, DC: World Bank. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31805 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

Figure 4: Germanwatch, https://www.germanwatch.org/sites/default/files/Global%20Climate%20Risk%20Index%202021_2.pdf

Figure 5: Source: IEA (2020). Projected Costs of Generating Electricity. https://www.iea.org/reports/projected-costs-of-generating-electricity-2020. All rights reserved.