This blog series aims to debunk ‘myths’ about trade-offs between climate action and development. Addressing political decision-makers, practitioners in multilateral development banks as well as staff of civil society organisations and the interested public, three blog posts will provide them with evidence to refute widespread misconceptions about the effects of climate action on development. They will also include recommendations for multilateral development banks on how to contribute to strengthening the link between climate action and development and thereby highlight win-win opportunities and avoid trade-offs.

Thomas A. Edison said as early as in 1931, “I’d put my money on the sun and solar energy. What a source of power! I hope we don’t have to wait until oil and coal run out before we tackle that.”[1] Nearly one century later, Edison’s hopes are more up-to-date than ever. Yet, some policymakers still believe that renewable energy generation contradicts a fast expansion of energy access and cannot provide reliable energy supply at all times. These concerns are widespread in Low- and Middle--Income Countries (LMICs), where energy policy is primarily linked to providing energy supply as quickly and economically as possible.

The COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war against Ukraine have disrupted global energy markets, putting energy security and the rapid transition to renewable energy sources yet again at the centre of debate. Most LMICs remain vulnerable to high and strongly fluctuating energy prices, and are dependent on the oil-exporters’ cartels.[2] This makes a fast transition to renewable energy supply that is based on decentralised and national resources even more urgent and important.

PROVIDING SECURE ENERGY ACCESS BASED ON RENEWABLE ENERGY IS A FAST, RATHER THAN A SLOW, SOLUTION.

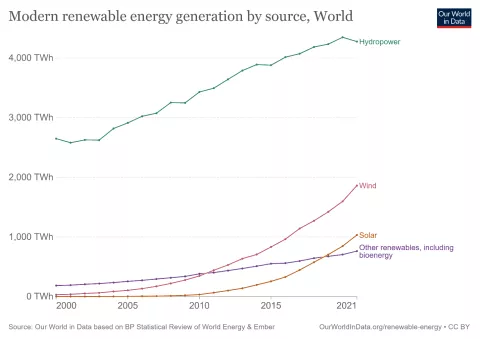

Some policymakers still fear that renewables cannot meet the rising demand for energy generation in time. However, there is more than enough evidence that this is a misjudgement. Technology development and dropping prices have triggered an investment boom in renewables:[3] Today, China has the largest solar energy, wind, hydro, and biogas capacity. Mexico, Indonesia, and Kenya, on the other hand, are leading producers of geothermal energy while South Korea takes the front rank in tidal energy production. Prices for renewables have dropped significantly over the last years, that is, for solar PV by 56%, for onshore wind by 45%, and for battery storage by 64% (2015-2020).[4] Between 2015 and 2019, renewable energy generation thus rapidly increased on a global scale; in the case of solar PV by 170% (to 680 TWh) and of wind by 70% (to 1,420 TWh), respectively.[5] In short, investments in renewables are growing faster than investments in traditional energy sources.[6]

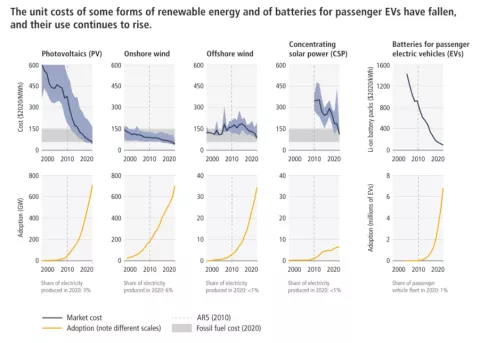

In most parts of the world, it is cheaper to generate power from PV and wind than from fossil fuels.[7] The following graph shows the steep cost decrease of the main types of renewables that led to this boom. As further cost decreases are expected, the slow replacement of fossil energy generation by renewables is very likely to continue.

Source: IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA.

In this respect, other than being fully inconsistent with the Paris Agreement, future coal-fired power plants will most likely never be able to operate economically under market conditions – without the use of subsidies. Both high coal prices and rising prices for fossil gas will further reduce the competitiveness for fossil fuel use in energy generation.[8] Even in major oil and gas producing countries, both fuel sources are expected to become less and less competitive – or already are in the case of oil.[9] Therefore, multilateral development banks (MDBs) are now focusing on an accelerated energy transition. The Asian Development Bank, for instance, promotes its Energy Transition Mechanism as a scalable, collaborative initiative. Using a market-based approach, it accelerates the transition from fossil to renewable energies, including the early retirement of coal plants. Development partners shall thereby guarantee low-cost funding to make the transition just and affordable.[10]

Decentralised production, such as off-grid solutions, is particularly attractive for countries with a weak power grid. Between 2000 and 2005, the number of people supplied with off-grid renewables increased six fold [11], and the percentage of countries with poor access to energy that have taken measures for mini-grid and off-grid systems surged from 15 to 70 percent.[12] Enhanced reliability, dropping energy costs and supportive climate policies have turned stand-alone and mini-grid renewable electricity into viable solutions for 80% of rural areas.[13] They are an effective mainstream source of energy extending the access to energy services to remote areas, and thus represent a promising opportunity for the rural population in many LMICs.[14] [15] The rapid deployment of renewables (especially wind, solar, and small hydro) therefore plays a key role for LMICs to secure rapid access to electricity.

Example: Vietnam’s rapidly growing renewable sector

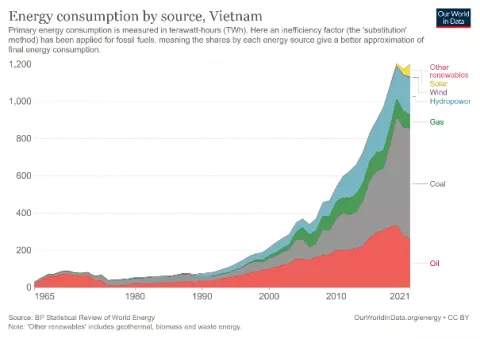

Vietnam has undergone tremendous economic growth since the economic and political reforms in 1986 (Đôi Mói.[1]).[16] It reports an average annual growth rate of 6% [17] that comes with a great demand for energy that is yearly increasing by 12%.[18] Coal is still the major source of energy generation, making up 51% of the total energy generation capacity [19], while hydropower represents the largest renewable source with a share of 27.7% (2019).[20] The Government of Vietnam committed to phase out coal-fuelled power generation by 2040, reduce its energy import dependency, and cut its greenhouse gas emissions.[21] This journey has started as a success story: Vietnam quadrupled the capacity of wind and solar energy power since 2019 and aims to become carbon neutral by 2050.[22]

Since 2018, Vietnam has introduced a series of feed-in tariffs to encourage the development of wind and solar projects.[23] By 2045, wind and PV shall contribute 50% to the energy mix.[24] Striving for such ambitious targets, Vietnam faces various transmission and infrastructure challenges. MDBs support the country in upgrading the national transmission network, developing hydraulic energy storage, and avoiding disruptions between wind and solar integration.[25] The World Bank, for instance, helps to improve Vietnam’s grid capacity for a better integration of renewable power generation.[26] Technical assistance and loans issued by the Asian Development Bank furthermore support the development of the power grid and Vietnam’s transition to clean power on more general terms.[27]

[1] Vietnamese for renovation or innovation.

IN A FAST-CHANGING WORLD, RENEWABLES ARE MORE RELIABLE THAN FOSSIL FUELS WHEN IT COMES TO ACHIEVING ENERGY SECURITY.

Another misconception is that renewables are not able to provide energy access for all at all times. While it is true that renewables depend on weather conditions, security of supply does not depend on them but results from integrated energy systems, including storage facilities and a variety of power sources. Apart from being large in number and geographically widespread, these need to be local, abundant, available, and affordable.[28] Renewable energy is a reliable source: it will always be present.

Furthermore, building up an energy system based on domestic renewable energy sources is less risky than remaining dependent on energy imports in terms of energy security. With a greater share of renewables in their energy mix, LMICs can diversify their energy supply and protect themselves from fluctuating prices of imported fossil fuels and changing international laws and trade agreements. In view of ever-growing energy needs in emerging economies [29], global energy demands ballooning by 30% by 2035 [30], and highly volatile prices on international fossil fuels markets, renewables thus represent a solid strategy to achieve energy security. This is especially the case in a world where limiting energy access is used as a weapon in conflicts or wars and fragile supply chains are disrupted due to external shocks.

In addition, fossil energy infrastructure will very likely turn into stranded assets as there are hardly any investors left to finance conventional coal power plants. For other fossil fuels such as oil and fossil gas, the IEA predicts that no new fields are needed, apart from existing or approved exploration sites, and that – because of gradually declining demand - many fields are expected to be closed for some time or even permanently until 2030, which will be reflected in by a decrease in investment.[31]

Renewables have proven to be an appropriate base energy source in many LMICs. In South Africa for example, the development of the largest baseload renewable energy project on the African continent is on the way. The project is aimed to be one of the worldwide largest solar and battery facilities, expected to provide major benefits for both the economy and energy sector.[32] However, they must be connected through a suitable energy grid. With falling prices for electricity storage [33], LMICs can add large-scale battery storage, especially for solar PV and wind power.[34] This is a great opportunity to leapfrog to state-of-the-art power generation technologies and combine off-grid and on-grid solutions. Thereby, LMICs can secure clean, affordable, round-the-clock power even in remote areas, which is an essential prerequisite to achieve the SDGs. [35]

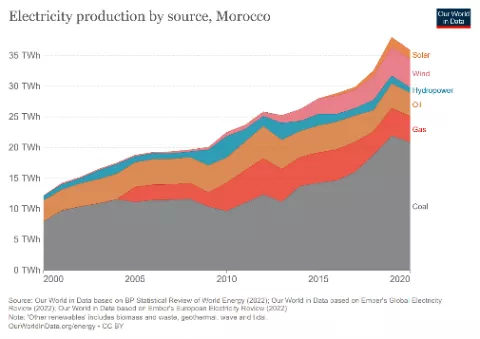

In short, renewables are more than able to provide enough energy for everyone and on a constant level. In order to benefit from this carbon-free, competitive, and reliable power, LMICs must set up ambitious policy targets to promote renewable energy generation and technology development. Besides Vietnam, Morocco’s introduction of solar and wind energy into their energy mix presents a good example.

Example: Solar and wind as the new backbone of energy supply in Morocco, replacing coal

Like many other countries, Morocco heavily relied on imported fossil fuels. As the country continues to experience growing energy demands and rising challenges posed by climate change, the Government of Morocco has diversified its energy generation mix with renewables, especially solar and wind sources. This approach has led to a significant reduction of the dependence from imported fuels.[2]

The government also took advantage of low oil prices and started to phase out fossil fuel subsidies. The money that was saved in this process was invested in education and health insurance. In 2021, Morocco’s NDC was updated and the renewable energy trajectory was raised to 52% by 2025 and to 64% by 2030.[36] At COP26 in Glasgow, Morocco pledged not to build new coal-fired power plants and confirmed its role as a climate leader among LMICs. [37] The Climate Action Tracker rates Morocco’s climate policies and actions as nearly compatible with the 1.5°C Paris Agreement but not yet sufficient for getting on a net-zero emission pathway: To achieve long-term decarbonisation, Morocco needs to accelerate the phase-out of coal-based electricity generation with international support. [38]

In view of steeply rising natural gas prices, it is also likely that Morocco will revise its plans to enhance the share of gas in the national energy matrix and accelerate the renewable energy uptake instead. Apart from the extension of solar power (PV and Concentrated Solar Power), as laid down in the Morocco Solar Plan, the Morocco Integrated Wind Energy Program is gaining momentum, too.[3]

In the Noor-Ouarzazate Power Station in Morocco, solar PV and CSP were joint for the first time to form a hybrid system, which produces approximately 80% of Morocco’s total solar power generation.[39; p.173,316] Concerning wind energy, the installed capacity in Morocco 2020 represented 22% of all of Africa’s generated wind energy. [40; p.44]

An important factor for Morocco’s successful energy transition is its strong institutional framework, including the Moroccan Agency for Sustainable Energy (MASEN), which has now taken the lead in the development of all renewable energy projects. However, there are still challenges that need to be tackled. For instance, Morocco should put more focus on small-scale projects providing solutions for the specific needs of individuals, small and medium size businesses, and regions in the future. For this to happen, regulation that would allow people or industries to easily implement their own renewable projects is still lacking.

MDBs and climate funds are the key investors in Morocco’s energy transition. The EUR 53.5 million loan provided by the EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) and the Climate Investment Fund for repowering Africa’s oldest wind farm Koudia Al Baida recently illustrated this.[41] These investors could provide more support for small-scale projects to support an energy transition that is more diversified and owned by the people.

[2]In 2020, installed capacity of renewables already reached 3,934 MW or 37% of Morocco’s energy mix.

[3] At the end of 2019, Morocco had 1.2 GW of installed wind capacity, without having exploited its vast offshore wind energy potential, which was estimated by the World Bank at up to 200 GW. Furthermore, an extension of the Morocco Hydroelectric Plan is envisaged beyond the 1.8 GW in hydro-electric capacity (2019), focusing on small and micro hydropower plants (100 kW to 1,500 kW).

MULTILATERAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS ARE DOING MORE, BUT NOT ENOUGH, FOR THE CONVERSION AND EXPANSION OF ENERGY SUPPLY BASED ON RENEWABLES.

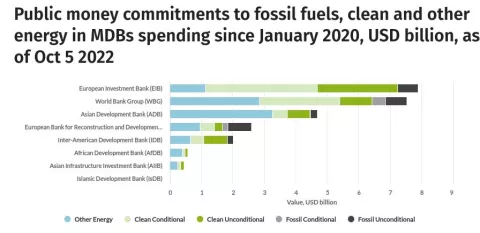

With about 840 million people still lacking access to electricity, MDBs are increasingly turning to renewables to contribute to SDG 7, which calls for affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all by 2030 [42]: The European Investment Bank (EIB), for instance, invested EUR 21 billion in (mostly large-scale) renewable energy projects between 2015 and 2020 as it considers access to energy a key to economic development.[43] The World Bank, on the other hand, committed to investing USD 1 billion to accelerate investments in battery storage for electric power systems in LMICs [44] and USD 1,110 million for electricity network reinforcement and energy access in 2018.[45] These strategic investments triggered the mobilization of another USD 4 billion in concessional loans [46], which are expected to lead to a threefold increase in battery storage by 2025. [47]

Source: Energy Policy Tracker, https://www.energypolicytracker.org/institution_analysis/mdbs/

The seven major MDBs have pledged to consistently gear their investments towards achieving the Paris climate targets. The shift in power investments is a first step towards fulfilling the pledge, but it is certainly not enough. [48] Even six years after their commitment, ADB, EBRD, EIB, IDB, and WB continue to invest in fossil energy projects, with current cumulative financial fossil energy commitments of about USD 3 billion (cf. figure 6).

- MDBs need to move much faster. They should end fossil fuel investments immediately, acting as true climate banks that make providing technical and financial support for a fast energy transition towards renewables their core business.

- In countries with limited energy access, MDBs can provide grid-based and off-grid electrification initiatives that alleviate and potentially overcome the current challenges in the field of reliable and accessible energy.[49] By increasing their financial support for the transition from fossil fuels to renewables, MDBs would avoid costly carbon lock-in [50] and ensure net social and economic gains for the long-term benefit of LMICs.[51] Altogether, more than USD 1 trillion in annual investments by 2030 would be necessary to accelerate global access to clean, affordable and reliable energy.[52] MDBs should offer concessional loans and tailored financial instruments for research, development and innovation, and financial support to achieve consistent electricity prices for on- and off-grid renewable energy. [53] [54]

- Furthermore, MDBs can improve energy frameworks and promote market attractiveness and competition by providing technical assistance and quality assurance to the private and public sectors. MDBs can also help to solve many of the challenges of the transition to clean energy, such as:

- insufficient power generation capacity;

- weak transmission and distribution infrastructure;

- high costs of energy supply to remote areas;

- lack of affordability for poorer households; and

- lack of financing for off-grid entrepreneurs [55]

This can be achieved by improving the financial, operational, and institutional environment with long-term system-wide planning; improving inclusive and tailored approaches to develop renewable power generation; and offering market solutions such as promoting optimised Feed-in Tariffs or Public-Private Partnerships (PPP).[56] MDBs can also provide LMICs with technical knowledge transfer on the integration of renewable energies with mapping, planning, and forecasting, partnership development as well as services of data collection and information sharing. [57]

- MDBs should further help set up an architecture to enhance the development of small-scale energy solutions that – compared to large-scale solutions – help increase the affordability of energy. Moreover, this would entail benefits for socio-economic development, for example employment opportunities and resilience to volatile energy prices. When reviewing their energy strategy policies, MDBs should make sure to allocate a percentage of energy-related funding to these small-scale solutions, support the establishment of financing facilities to that effect, and provide technical assistance. Lastly, MDBs should assist financial intermediaries not only in increasing investment in small-scale energy technologies but also in improving the availability of investment data. [58]

In short, MDBs are in an excellent position to support their partner countries’ energy transitions while at the same time fulfilling their development mandate by further strengthening the manifold win-win elements between climate action and development.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

• Climate action, energy security, and economic efficiency make renewable energies the future of the energy sector. They represent a local, abundant, clean, and affordable source of energy that keeps LMICs from high and volatile fossil fuel prices, dependence on energy exporting countries, and a negative foreign trade balance. And even in those countries that are reliant on oil and gas exports, renewables have huge future potential. According to the IEA, the levelised cost of electricity base of solar PV is already competitive with oil in the Middle East and North Africa regions, and will likely be competitive with fossil gas by 2030.[59] The rapid deployment of renewables, especially wind and solar PV, therefore grants LMICs secure, rapid, reliable, and cost-efficient access to electricity, even in remote areas with limited access to the power grid. Investments in renewables also pose a lower investment risk than fossil fuel-fired power plants.• In view of an accelerating climate crisis and increasing geopolitical cleavages, LMICs should speed-up rather than delay the integration of renewables in their national power mix. They should pursue the ambition of switching to 100 per cent renewable energy supply by 2050.

• Development partners should support the energy transition in LMICs by means of climate partnerships as well as by providing technical and financial support and preferential market access.

• MDBs should end fossil fuel investments immediately, acting as true climate banks that make providing technical and financial support for a fast energy transition their core business.

• Civil society organisations play an important role to play in building trust in renewables. They can successfully pioneer innovative solutions, build energy transition alliances with other stakeholders, and mobilise broad social support for a fossil-free energy future.