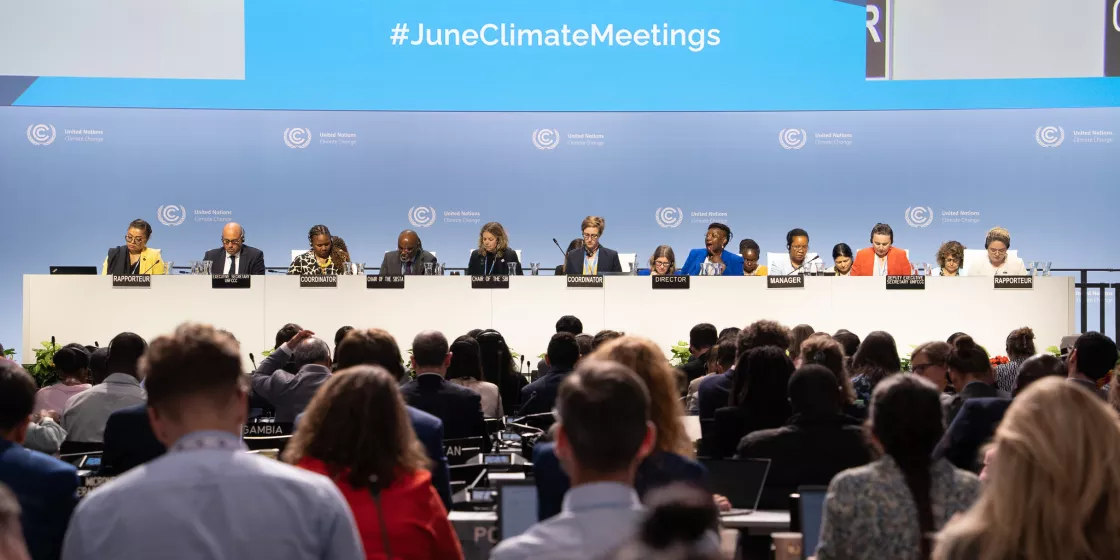

Die 62. Sitzungen der UN-Klimaverhandlungsorgane (SB62) fanden im Juni 2025 in Bonn statt und stellten die Weichen für die COP30 in Brasilien. Technische Fortschritte wurden erzielt, etwa beim Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) und dem Just Transition Work Programme (UAE JTWP), politische Durchbrüche blieben jedoch aus. Besonders kritisch sind die Umsetzung der JTWP, das Ambitionsdefizit der nationalen Klimaziele (NDCs) und die Bereitstellung ausreichender Klimafinanzierung für Anpassung und Verluste & Schäden (L&D).

Die brasilianische COP30-Präsidentschaft muss nun konkrete Schritte vorlegen, um diese Themen bis November erfolgreich abzuschließen.

Unsere Expert:innen für internationale Klimapolitik ordnen die Ergebnisse der Zwischenverhandlungen in diesem englischsprachigen Blogbeitrag ein.